‘You never get that smell off your clothes.’

Jesus, 24 | El Paso, TX

Jesus immigrated to El Paso from Chihuahua City when he was ten years old. “You know, it was in 2005. And it was kind of the first wave of violence down in Mexico. And my dad lost his job. A lot of people here are from Chihuahua. It’s a lot safer here.” He’s been sorting cattle around the US-Mexico border since dropping out of college. “I went to work for a Mexican cattle broker. So he just buys cattle imported to the United States from Mexico. I started off just pushing cattle and then started moving up. Now I’m the manager there at the pens.”

He goes by ‘Chuy’ around his friends and coworkers. “I’m the youngest one at the pens. That can be a problem if you make it one, you know? People just see you’re young and sometimes they don’t respect you, but it’s only if you let it happen.”

Due to pandemic closures of processing plants and drought, Jesus and his older coworker Toño became overburdened by work in the winter.

Note: These interviews with Jesus and Toño were conducted separately over the course of several days in English and Spanish. Translations are in brackets.

____

Jesus: I knew this is what I wanted to do all my life. I like that I get to wake up every morning and I don’t have to go to an office to punch the clock, put my eight hours in and leave. I get to go outside, get to the pens. I get to be around cattle. I mean, some people hate it. Some people have no idea what it’s like, they don’t even know the smell. [Laughs.] The cattle business changes every day because it’s not a product, you know, it’s an actual animal. They’re living creatures and we’re supposed to take care of them. It’s like having 1,000 pets. I think that’s something to take a lot of pride in. We get to see where our food comes from.

I was real thankful that we continued going to work because I’m an essential worker, you know, because of agriculture. This winter we were operating over capacity by almost 100% because we couldn’t sell the cattle, plus the price of alfalfa, hay, everything has been real high because there’s no water. A bunch of people are pumping their wells dry. So we had extra work, but we weren't resentful because we all enjoy our job. We didn’t have cuts in pay or anything. We were really blessed to just keep going.

Cattle cross the US-Mexico border wall at the Santa Teresa crossing in southern New Mexico.

Toño watches cattle cross the border.

Toño: Este año tuvimos más trabajo que los otros años. Una cosa fue la pandemia y otra cosa fue la sequía. Fueron dos variables muy fuertes. Por la sequía, muchos no tuvieron manera de alimentar su ganado. La gente se tenía que deshacer de los animales. Y por la pandemia, se hizo más difícil vender los animales y se acumularon.

Es que... la compraventa del ganado Mexicano se rige desde las plantas procesadoras. A la ora que la pandemia te cierra plantas procesadoras, te cierra supermercados, te cierra muchas cosas, y se va mucho la cadenita hacia atrás. La planta procesadora ya no le está comprando a la engorda. La engorda ya no le compra a los compradores de la frontera. Los compradores de la frontera ya no le compran al productor Mexicano. Empieza a haber muy poca manera de mover el ganado. Ganaderos no tienen donde ponerlos, donde moverlos, a quien venderle. Ni nosotros como compradores. No podemos hacer corrales y corrales viendo a ver cuando se va vender. Por eso estamos sobre capacidad. El supermercado es el único que gana porque tiene la capacidad para guardar todo ese producto empaquetado en congeladores hasta que se abra otra vez el mercado.

Vi a los demás con muchísima presión. A Jesus le toco mucho más tiempo trabajando.

Es que... la compraventa del ganado Mexicano se rige desde las plantas procesadoras. A la ora que la pandemia te cierra plantas procesadoras, te cierra supermercados, te cierra muchas cosas, y se va mucho la cadenita hacia atrás. La planta procesadora ya no le está comprando a la engorda. La engorda ya no le compra a los compradores de la frontera. Los compradores de la frontera ya no le compran al productor Mexicano. Empieza a haber muy poca manera de mover el ganado. Ganaderos no tienen donde ponerlos, donde moverlos, a quien venderle. Ni nosotros como compradores. No podemos hacer corrales y corrales viendo a ver cuando se va vender. Por eso estamos sobre capacidad. El supermercado es el único que gana porque tiene la capacidad para guardar todo ese producto empaquetado en congeladores hasta que se abra otra vez el mercado.

Vi a los demás con muchísima presión. A Jesus le toco mucho más tiempo trabajando.

Toño: [This year we had a lot more work than other years. One reason was the pandemic and the other was the drought. They were two really strong variables. Because of the drought, many didn’t have a way to feed their cattle. People had to get rid of their animals. And because of the pandemic, it was harder to sell the animals and they accumulated.]

[You see, Mexican cattle trading is dependent on the processing plants. As soon as the pandemic closes processing plants, it closes supermarkets, it closes a lot of things, and the chain starts to run back. The processing plant no longer buys from the feedyard. The feedyard no longer buys from brokers at the border. The brokers at the border no longer buy from the Mexican producers. There start to be very few ways to move the cattle. Ranchers have nowhere to put them, nowhere to move them, no one to sell to. And neither do we as brokers. We can’t just build more and more corrals waiting to see when the cows will sell. That’s why we’re over capacity. The supermarket is the only one who wins because they have the capacity to store all that packaged product in freezers until the market opens up again.]

[I saw everyone with a lot of pressure on them. Jesus had to spend much more time working.]

[You see, Mexican cattle trading is dependent on the processing plants. As soon as the pandemic closes processing plants, it closes supermarkets, it closes a lot of things, and the chain starts to run back. The processing plant no longer buys from the feedyard. The feedyard no longer buys from brokers at the border. The brokers at the border no longer buy from the Mexican producers. There start to be very few ways to move the cattle. Ranchers have nowhere to put them, nowhere to move them, no one to sell to. And neither do we as brokers. We can’t just build more and more corrals waiting to see when the cows will sell. That’s why we’re over capacity. The supermarket is the only one who wins because they have the capacity to store all that packaged product in freezers until the market opens up again.]

[I saw everyone with a lot of pressure on them. Jesus had to spend much more time working.]

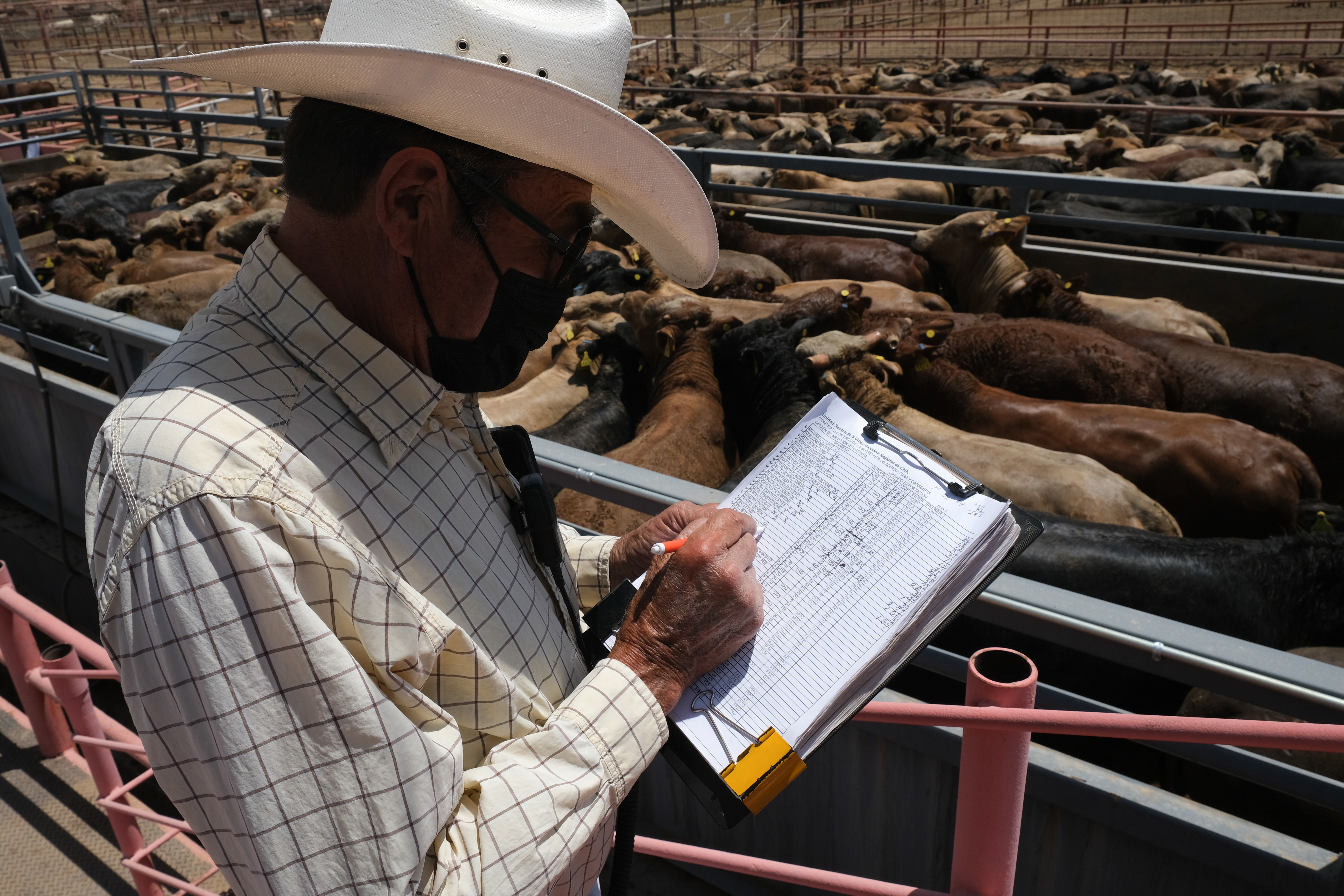

A manager keeps count of Mexican livestock imports. 2,000-5,000 cattle cross into the facility every day.

Jesus: Tuve un día muy cabrón güey. [I had a really brutal day, dude].

It was probably December or January so it was cold, man. And we got cattle in from Douglas and Presidio, about 10 trucks. That’s like 1,200 or 1,300 head total. On a normal day we probably get like four or five trucks, but we don’t process all of them. That’s the difference. Like we might sort two or three trucks, you know, but on this day we had like 10 or 11. I can’t even remember. I knew the day before that we were going to be receiving a lot of trucks to sort, but I didn’t know that we were going to process them all and ship them out that same day.

To process cattle, you gotta brand, tag, dehorn, and vaccinate. I started off branding and then we switched off because there was a lot of cattle, man. We had to be rotating all the time. So you’re branding and you got all the smoke in your face, all the hair burning and everything. Like if you’ve ever burnt yourself? That’s what it smells like. I probably went through like 500 steers. I was getting dizzy from all the smoke. And if you’re pushing cattle through the chute you’re yelling all the time. If you’re putting in vaccines, your hands start cramping up. You start getting tired of that. You just gotta switch, you gotta rotate.

We had been working all day, since seven in the morning, and we were so tired. Then at night it got cold, like in the 20s, and it started raining sleet. We were all wet. The hot shot, which is like a taser we use to shock the cattle so they start moving, that thing got all wet and it started shocking our hands. So we started taking turns because we couldn’t take it that long.

We finished processing at like 11:30 at night and didn’t finish loading the trucks until 1:30 in the morning. By the time you get home, you take your clothes off, you get in the shower. The bathroom stinks. It’s like you processed all the head in your bathroom. You never get that smell off your clothes. My wife already knows; she’s used to it. Plus you’re all covered in blood from cutting up horns and everything gets dirty.

At the end of the day, you’re glad you got that job done. But you still gotta be back at the pens at 7:30 in the morning, ready for the next day.

A snowy day at the pens in Anthony, NM where Jesus and Toño work. Video courtesy of Toño Marquezhoyos.

Toño: Jesus is the youngest one at the pens. In the old times I think it was more easy to find young people to work in the cattle business, but not now. The new young people is very lazy. They got a lot of variance to choose in the city. They got a lot of things they can do in the shade instead of being outside.

La generación de Jesus, o Jesus en sí, está respondiendo de manera diferente a la pandemia porque se acaba de casar; acaba de tener otro compromiso. Antes de tener un compromiso de ese tamaño, de formar una familia, tu mente no es la misma. Tu mente es más ególatra, buscas tu propio bienestar. Ahorita no puedes buscar tu propio bienestar porque tienes a quien depende de tí. Ahora tienes que ser protector, tienes que ser proveedor, tienes que ser una figura de que es lo que quieres dejar, que es lo que quieres transmitir a tu gente, tu familia.

Jesus está en la transición de ese cambio. Ahorita como no le han soltado muy bien la rienda los papás ni los suegros todavía los tienen muy pegados. No se ha dado cuenta lo que es estar solo. Cuando se te acaban los papás, allí es cuando realmente dices “Caray estoy solo. Ahora si tengo que valerme por mí mismo. Ya no hay quien me ponga la teta.” Eso es lo más duro.

Jesus está en la transición de ese cambio. Ahorita como no le han soltado muy bien la rienda los papás ni los suegros todavía los tienen muy pegados. No se ha dado cuenta lo que es estar solo. Cuando se te acaban los papás, allí es cuando realmente dices “Caray estoy solo. Ahora si tengo que valerme por mí mismo. Ya no hay quien me ponga la teta.” Eso es lo más duro.

[Jesus’s generation, or rather Jesus himself, is responding differently to the pandemic because he just got married; he just made another commitment. Before making a commitment of that size, before forming a family, your mind is not the same. You’re egotistical, you seek your own well-being. Now you can’t seek your own well-being because you have someone who’s dependent on you. Now you have to be the protector, you have to be the provider. You have to be a figure of what you want to leave behind, what you want to pass down to your people, your family.]

[Jesus is in the transition of this change. Right now, since his parents haven’t really let go of their rein, nor his in-laws; they still have him really close. He hasn’t realized what it is to be alone. When you lose your parents, that's when you really say “Wow, I’m alone. Now I have to fend for myself. There’s no one to give me the tit.” That’s the hardest thing.]

[Jesus is in the transition of this change. Right now, since his parents haven’t really let go of their rein, nor his in-laws; they still have him really close. He hasn’t realized what it is to be alone. When you lose your parents, that's when you really say “Wow, I’m alone. Now I have to fend for myself. There’s no one to give me the tit.” That’s the hardest thing.]

Toño (right) and Jesus (left) take a break from driving on their way to Del Rio, TX.

Jesus: I got married in August of 2019 and I have a baby girl. She’s gonna be ten months old. Her name’s Ana Lucia. All through the pregnancy, since the pandemic was going on, my wife wasn’t able to get her mom or her sisters involved in helping out. So we learned a lot and I think it helped us grow in our marriage.

For the birth of my daughter, it was just me and my wife in the hospital. If I saw it through someone else’s eyes, we probably looked like kids, like deer in the headlights, you know? We were just a couple kids not knowing what’s going on and…. I mean, we made it. People always find it weird that we’re so young and married and have a kid. The thing is people nowadays are not even getting married until they’re like 30. Fewer are having kids.

The hardest part about being a parent is balancing work and life, work and family. Sometimes… not sometimes. You always got to work, you know? There’s no other way around it. You’re just working for money, so if you work more, you get more money… and if you do a good job, you get recognized for it. You just need to know when enough is enough. I’m getting to it. At some point, you just gotta realize I wanna see my baby girl. I wanna see my baby take her first step.

Translated by Alan Jinich

El Paso, Texas

Interview Date: May 25-29, 2021